若き日の森山さんと河井寛次郎先生の写真。夏の休みに、家族で訪れた海水浴場にて。(*1)

*1_ Picture of a younger Moriyama-san and Kanjirou Kawai. Visiting the beach with the family during summer vacation.

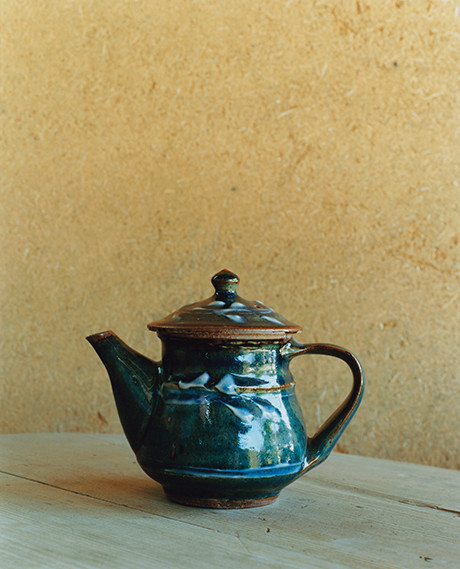

いい焼き物には、内側から静かに光が射している。

Good pottery is when light shines softly from within.

いい焼き物には、内側から静かに光が射している。

Good pottery is when light shines softly from within.

石見銀山の湯治の湯として栄えた温泉津温泉街からすぐの丘の上に森山窯はある。穏やかに陽光を遮るように庇の長い瓦屋根が伸び、柔らかい光の回る室内では、ラジオの音が静かに響く。陶工の森山雅夫さんが轆轤を挽いている。

民藝運動の中心的なメンバーとして用の美を陶芸作品に見出し、戦後にはさらに圧倒的な彫刻作品を生み出していった河井寛次郎。森山さんは、その河井寛次郎の最後の内弟子として、6年の間、一緒に暮らしたことがある。

師匠と弟子。森山さんに尋ねたのは、そこにどんな人間関係が構築され、何が伝えられたのか。

民藝運動の中心的なメンバーとして用の美を陶芸作品に見出し、戦後にはさらに圧倒的な彫刻作品を生み出していった河井寛次郎。森山さんは、その河井寛次郎の最後の内弟子として、6年の間、一緒に暮らしたことがある。

師匠と弟子。森山さんに尋ねたのは、そこにどんな人間関係が構築され、何が伝えられたのか。

Moriyama’s kama (furnace) is located at the top of the hill right outside the Yunotsu Onsen district. Eaves of the tiled roof stretch out and block off the sunlight while the sound of the radio radiates softly within the walls. Potter, Masao Moriyama, is at the potter’s wheel.

At the center of the Mingei Movement was a master potter named Kanjiro Kawai, who was a pioneer of expressing “functional beauty” in ceramics and produced even more overwhelming pieces in the postwar period. Moriyama-san was Kanjiro Kawai’s last apprentice and lived together with him for six years. We asked Moriyama-san about the master and apprentice relationship.

At the center of the Mingei Movement was a master potter named Kanjiro Kawai, who was a pioneer of expressing “functional beauty” in ceramics and produced even more overwhelming pieces in the postwar period. Moriyama-san was Kanjiro Kawai’s last apprentice and lived together with him for six years. We asked Moriyama-san about the master and apprentice relationship.

「ものをよく見ろ」と教えられた。

He said, “observe objects closely.”

「ものをよく見ろ」と教えられた。

He said, “observe objects closely.”

「先生は人のいいところを見つけ出す人でした。本当に家族同然のようにして生活させてもらいました」

そう言って森山さんが持ってきてくれたのは、福井県の高浜へ河井寛次郎の娘や孫たちと一緒に海水浴に行ったときの写真。森山さん30歳を過ぎた頃。海パン姿のふたりからは、師弟関係は見えてこない。日常でも、朝9時過ぎに起きてくる河井先生と、まず一緒にお茶をしていた。食事も一緒。その生活の合間に、かけがえのない瞬間があった。

「これはよく焼けている、これはちょっと生焼けだとか、窯出しの時に、それくらいは分かるようになっていたころのことです。自分としてはこっちの方がもっとよく焼けているのになっていうものとは違うものを、河井先生は『枕元に持って上がってくれ』と言われたんです。夜に先生の背中を揉みにいったり、浮かんだアイディアを書き付けた先生のメモを取りに行ったり、その度に枕元に置いてある、その窯出しのときのものを見ることになる。もっと違うものがあるのにと思っていたのが、ある時に、先生が言われる通りに『こういうものがいいもんだな』と自分なりに気がついたんですよ。焼き物っていうのは表面の光ではなしに、中から静かな光が射しているっていうことが自分なりに分かってきたんです」

そう言って森山さんが持ってきてくれたのは、福井県の高浜へ河井寛次郎の娘や孫たちと一緒に海水浴に行ったときの写真。森山さん30歳を過ぎた頃。海パン姿のふたりからは、師弟関係は見えてこない。日常でも、朝9時過ぎに起きてくる河井先生と、まず一緒にお茶をしていた。食事も一緒。その生活の合間に、かけがえのない瞬間があった。

「これはよく焼けている、これはちょっと生焼けだとか、窯出しの時に、それくらいは分かるようになっていたころのことです。自分としてはこっちの方がもっとよく焼けているのになっていうものとは違うものを、河井先生は『枕元に持って上がってくれ』と言われたんです。夜に先生の背中を揉みにいったり、浮かんだアイディアを書き付けた先生のメモを取りに行ったり、その度に枕元に置いてある、その窯出しのときのものを見ることになる。もっと違うものがあるのにと思っていたのが、ある時に、先生が言われる通りに『こういうものがいいもんだな』と自分なりに気がついたんですよ。焼き物っていうのは表面の光ではなしに、中から静かな光が射しているっていうことが自分なりに分かってきたんです」

“It didn’t matter the person, Kawai-sensei was able to find the best in everyone and bring it out. At least that is what I think, but we actually just lived as if we were family. I brought a picture of us in the summer.”

Moriyama-san brought out a picture of a swimming trip to Takahama in Fukui prefecture that he made with Kanjiro Kawai and his family. Moriyama-san was in his 30s at the time. Both in their swimming trucks, they seemed more like father and son or grandfather and grandchild than they did master and apprentice. Even in their daily routine, Moriyama-san would have tea in the mornings with Kawai-sensei and they ate their meals together as well. Moriyama-san had an invaluable experience while living this lifestyle.

“It was at a time when I was finally able to tell the difference between ceramics that were fired well or under fired out of the kiln. To me it felt like this one was fired better, but I would be wrong, and Kawai-sensei said to place the better one next to his pillow. I would often go to his room to rub his back, or to fetch his idea notebook, and I would always see the objects placed in his room near his pillow. I would think to myself, ‘there are better pieces than these…” but I then realized, it was exactly as Kawai-sensei said, “these are the good pieces.” Good ceramics aren’t just the ones that shine brightly on the outside, but are the ones where the light shines gently from within.”

The master said, “observe objects closely.” Because you do not yet know what is good, take items that you think are good and look at them over and over. Moriyama-san underwent a vicarious experience “observing” the world through his master’s eyes and learned that the true essence of pottery did not just live in the beauty of the exterior surface.

“He would tell me to make a teacup, and I would go make one but it wouldn’t turn out well. I would say, ‘I can’t seem to spin it well,’ and of course that is so. Kawai-sensei’s friend, Shoji Hamada, taught me that, ‘pottery is making thousands and ten thousands, so of course you will not get a good result from only making ten or twenty. Pottery is repeating the process over and over and then you finally just get it.”

Moriyama-san brought out a picture of a swimming trip to Takahama in Fukui prefecture that he made with Kanjiro Kawai and his family. Moriyama-san was in his 30s at the time. Both in their swimming trucks, they seemed more like father and son or grandfather and grandchild than they did master and apprentice. Even in their daily routine, Moriyama-san would have tea in the mornings with Kawai-sensei and they ate their meals together as well. Moriyama-san had an invaluable experience while living this lifestyle.

“It was at a time when I was finally able to tell the difference between ceramics that were fired well or under fired out of the kiln. To me it felt like this one was fired better, but I would be wrong, and Kawai-sensei said to place the better one next to his pillow. I would often go to his room to rub his back, or to fetch his idea notebook, and I would always see the objects placed in his room near his pillow. I would think to myself, ‘there are better pieces than these…” but I then realized, it was exactly as Kawai-sensei said, “these are the good pieces.” Good ceramics aren’t just the ones that shine brightly on the outside, but are the ones where the light shines gently from within.”

The master said, “observe objects closely.” Because you do not yet know what is good, take items that you think are good and look at them over and over. Moriyama-san underwent a vicarious experience “observing” the world through his master’s eyes and learned that the true essence of pottery did not just live in the beauty of the exterior surface.

“He would tell me to make a teacup, and I would go make one but it wouldn’t turn out well. I would say, ‘I can’t seem to spin it well,’ and of course that is so. Kawai-sensei’s friend, Shoji Hamada, taught me that, ‘pottery is making thousands and ten thousands, so of course you will not get a good result from only making ten or twenty. Pottery is repeating the process over and over and then you finally just get it.”

轆轤で挽かれ、乾かしている器。土の仕事。(*2)

*2_ Spinning at the potter’s wheel, dried vessels. Working with clay.

「ものをよく見ろ」と言われていた。とにかく何回も「目を皿のようにして見ろ」と。師匠の目を通した世界を追体験するように”見る“ことで、焼き物の本質は、表面の美しさだけに宿るものではないことを理解していく。

「湯のみを作ってくれと言われて、湯のみを轆轤で挽くんですがうまくいかない。『なかなかきれいに揃いません』と言ったら、それはそうだろうと。河井先生の盟友でもある濱田庄司先生の言葉を教えてくれました。『焼き物は千個万個の単位のものだから、10個や20個作っていいものができるはずがない。焼き物は繰り返しの仕事で、それでやっといいものができるんだから』と。ただ寸法さえ揃っていればいいというのではなしに、毎回いいものを作ろうという気持ちっていうかね。一個でも新しいものを作るんだっていうことが大事なんです。その作ったものが、生きているかどうかっていうことですよね。60年近く経った今でもその気持でやってますけれども(笑)」

”新しい自分が見たいのだ、仕事する“

河井寛次郎のこの言葉は、”新しい形“を追い求めた作家としての言葉として捉えられることが多いが、それだけではない。森山さんが教えられた通り、同じように湯のみをひとつ作る際にも、新しく自分に向かい合わなければならない。千個万個の単位であったとしても、少しずつ自分を更新していくように生きることを語った言葉。

「後から気づいたんですけれども、焼き物は千個万個の単位のものだからということは、『一職人の仕事をしていけよ』と言われたような気がしたんです。職人の仕事。人間国宝に推薦された時にも、自分なんかよりもいい仕事をされている職人さんたちがたくさんいるんだからとずっと辞退されていた人ですから。千個万個の単位というお話を聞いた時に、そう言われたのかなっていう気がしたんです」

焼き物に関わる部分だけではない。あらゆる細部に美意識がなければ、いいものは作れない。使われることの中に美しさを見出した民芸の根本は、やはり生活の中にある。

「河井先生は食べ物でも何でも大事にされます。日々のことは何でも。初めに掃除をしてくれと言われて、掃除をしたんです。雑巾とバケツを持って拭けば掃除だと思ってしたんです。後で先生が来られて、そこに置いてあった焼き物の方向を全部変えられる。『ものには向く方向と置き場所がある。それをきちんとしなければいけない』と言われました。それから、『掃除というものは、まず自分が気持ちいいんだろう』と。そこにいることが気持ちいいことが、掃除をすることだというようなことを言われました」

置く場所と向く方向がある。これは、焼き物だけについて当てはまる言葉だろうか? 森山さんが、「人生そのものを教わった気がする」と懐古するのは、こんな言葉にヒントがあるのではないか。焼き物という共通言語を用いて、人としての道のようなものを伝えていくような関係。

「湯のみを作ってくれと言われて、湯のみを轆轤で挽くんですがうまくいかない。『なかなかきれいに揃いません』と言ったら、それはそうだろうと。河井先生の盟友でもある濱田庄司先生の言葉を教えてくれました。『焼き物は千個万個の単位のものだから、10個や20個作っていいものができるはずがない。焼き物は繰り返しの仕事で、それでやっといいものができるんだから』と。ただ寸法さえ揃っていればいいというのではなしに、毎回いいものを作ろうという気持ちっていうかね。一個でも新しいものを作るんだっていうことが大事なんです。その作ったものが、生きているかどうかっていうことですよね。60年近く経った今でもその気持でやってますけれども(笑)」

”新しい自分が見たいのだ、仕事する“

河井寛次郎のこの言葉は、”新しい形“を追い求めた作家としての言葉として捉えられることが多いが、それだけではない。森山さんが教えられた通り、同じように湯のみをひとつ作る際にも、新しく自分に向かい合わなければならない。千個万個の単位であったとしても、少しずつ自分を更新していくように生きることを語った言葉。

「後から気づいたんですけれども、焼き物は千個万個の単位のものだからということは、『一職人の仕事をしていけよ』と言われたような気がしたんです。職人の仕事。人間国宝に推薦された時にも、自分なんかよりもいい仕事をされている職人さんたちがたくさんいるんだからとずっと辞退されていた人ですから。千個万個の単位というお話を聞いた時に、そう言われたのかなっていう気がしたんです」

焼き物に関わる部分だけではない。あらゆる細部に美意識がなければ、いいものは作れない。使われることの中に美しさを見出した民芸の根本は、やはり生活の中にある。

「河井先生は食べ物でも何でも大事にされます。日々のことは何でも。初めに掃除をしてくれと言われて、掃除をしたんです。雑巾とバケツを持って拭けば掃除だと思ってしたんです。後で先生が来られて、そこに置いてあった焼き物の方向を全部変えられる。『ものには向く方向と置き場所がある。それをきちんとしなければいけない』と言われました。それから、『掃除というものは、まず自分が気持ちいいんだろう』と。そこにいることが気持ちいいことが、掃除をすることだというようなことを言われました」

置く場所と向く方向がある。これは、焼き物だけについて当てはまる言葉だろうか? 森山さんが、「人生そのものを教わった気がする」と懐古するのは、こんな言葉にヒントがあるのではないか。焼き物という共通言語を用いて、人としての道のようなものを伝えていくような関係。

He said to, “observe objects closely.”

“It didn’t matter the person, Kawai-sensei was able to find the best in everyone and bring it out. At least that is what I think, but we actually just lived as if we were family. I brought a picture of us in the summer.”

Moriyama-san brought out a picture of a swimming trip to Takahama in Fukui prefecture that he made with Kanjiro Kawai and his family. Moriyama-san was in his 30s at the time. Both in their swimming trucks, they seemed more like father and son or grandfather and grandchild than they did master and apprentice. Even in their daily routine, Moriyama-san would have tea in the mornings with Kawai-sensei and they ate their meals together as well. Moriyama-san had an invaluable experience while living this lifestyle.

“It was at a time when I was finally able to tell the difference between ceramics that were fired well or under fired out of the kiln. To me it felt like this one was fired better, but I would be wrong, and Kawai-sensei said to place the better one next to his pillow. I would often go to his room to rub his back, or to fetch his idea notebook, and I would always see the objects placed in his room near his pillow. I would think to myself, ‘there are better pieces than these…” but I then realized, it was exactly as Kawai-sensei said, “these are the good pieces.” Good ceramics aren’t just the ones that shine brightly on the outside, but are the ones where the light shines gently from within.”

The master said, “observe objects closely.” Because you do not yet know what is good, take items that you think are good and look at them over and over. Moriyama-san underwent a vicarious experience “observing” the world through his master’s eyes and learned that the true essence of pottery did not just live in the beauty of the exterior surface.

“He would tell me to make a teacup, and I would go make one but it wouldn’t turn out well. I would say, ‘I can’t seem to spin it well,’ and of course that is so. Kawai-sensei’s friend, Shoji Hamada, taught me that, ‘pottery is making thousands and ten thousands, so of course you will not get a good result from only making ten or twenty. Pottery is repeating the process over and over and then you finally just get it.”

I want to see a new me, so I work.

Like Moriyama-san was taught, when you create a single teacup, you have to strive to recreate yourself at the same time. Even when making thousands or ten thousands of a single object, you yourself start to change little by little. This is what Kawai-sensei’s words mean.

“The idea that pottery is about making thousands or ten thousands of an object is like being told to go do the work of a craftsman. Work of a craftsman! Even when Kawai-sensei was recommended for a Living Legend award, he would think to himself that there must be hundreds of other craftsmen creating better work and he always turned down the award. I believe he told me those words the same time that I learned what pottery truly was.”

It is not just about pottery. If aesthetic sense does not exist in all of the details, you cannot create something good. The root of the beauty apparent when using folk craft is found within everyday life.

“Kawai-sensei puts great importance on everything. The first time he told me to clean, I cleaned. I thought that if I used a bucket and dust cloth, and then wiped things down, that was cleaning. Kawai-sensei came and changed the layout of all of the pottery. He told me that, ‘objects have a layout and orientation. You must adhere to them.’ He said that ‘cleaning is first making sure you feel good.’ After that, it is about if you feel good in that space.”

Objects have a place and orientation. Surely it was in reference to just pottery, right? But, as Moriyama-san recalls his human relationships he explains that the words describe a kind of relationship where a person’s life is portrayed through this shared language in pottery.

“It didn’t matter the person, Kawai-sensei was able to find the best in everyone and bring it out. At least that is what I think, but we actually just lived as if we were family. I brought a picture of us in the summer.”

Moriyama-san brought out a picture of a swimming trip to Takahama in Fukui prefecture that he made with Kanjiro Kawai and his family. Moriyama-san was in his 30s at the time. Both in their swimming trucks, they seemed more like father and son or grandfather and grandchild than they did master and apprentice. Even in their daily routine, Moriyama-san would have tea in the mornings with Kawai-sensei and they ate their meals together as well. Moriyama-san had an invaluable experience while living this lifestyle.

“It was at a time when I was finally able to tell the difference between ceramics that were fired well or under fired out of the kiln. To me it felt like this one was fired better, but I would be wrong, and Kawai-sensei said to place the better one next to his pillow. I would often go to his room to rub his back, or to fetch his idea notebook, and I would always see the objects placed in his room near his pillow. I would think to myself, ‘there are better pieces than these…” but I then realized, it was exactly as Kawai-sensei said, “these are the good pieces.” Good ceramics aren’t just the ones that shine brightly on the outside, but are the ones where the light shines gently from within.”

The master said, “observe objects closely.” Because you do not yet know what is good, take items that you think are good and look at them over and over. Moriyama-san underwent a vicarious experience “observing” the world through his master’s eyes and learned that the true essence of pottery did not just live in the beauty of the exterior surface.

“He would tell me to make a teacup, and I would go make one but it wouldn’t turn out well. I would say, ‘I can’t seem to spin it well,’ and of course that is so. Kawai-sensei’s friend, Shoji Hamada, taught me that, ‘pottery is making thousands and ten thousands, so of course you will not get a good result from only making ten or twenty. Pottery is repeating the process over and over and then you finally just get it.”

I want to see a new me, so I work.

Like Moriyama-san was taught, when you create a single teacup, you have to strive to recreate yourself at the same time. Even when making thousands or ten thousands of a single object, you yourself start to change little by little. This is what Kawai-sensei’s words mean.

“The idea that pottery is about making thousands or ten thousands of an object is like being told to go do the work of a craftsman. Work of a craftsman! Even when Kawai-sensei was recommended for a Living Legend award, he would think to himself that there must be hundreds of other craftsmen creating better work and he always turned down the award. I believe he told me those words the same time that I learned what pottery truly was.”

It is not just about pottery. If aesthetic sense does not exist in all of the details, you cannot create something good. The root of the beauty apparent when using folk craft is found within everyday life.

“Kawai-sensei puts great importance on everything. The first time he told me to clean, I cleaned. I thought that if I used a bucket and dust cloth, and then wiped things down, that was cleaning. Kawai-sensei came and changed the layout of all of the pottery. He told me that, ‘objects have a layout and orientation. You must adhere to them.’ He said that ‘cleaning is first making sure you feel good.’ After that, it is about if you feel good in that space.”

Objects have a place and orientation. Surely it was in reference to just pottery, right? But, as Moriyama-san recalls his human relationships he explains that the words describe a kind of relationship where a person’s life is portrayed through this shared language in pottery.

「頭の中で他のことを考えても作れるようになるのが、本当かなと思う」と森山さん。(*3)

*3_ Moriyama-san pondering if “can I still create something if I am thinking about something else?”

「初めに陶工になる前に、立派な人間になれと言われたんです。人間としての暮らしをしなさいよと。立派な人間とは、きちんと暮らしている人のことなのかな。ある時にふっと思い出しています」

「今の時代に合ったものを作りたい」と森山さんは言う。それが今の民芸ではないかと。世の中に有り余るほどのものの中から選ばれるためには、「ただ作ればええっていうもんじゃない」。表面の美しさではなく、中から光が漏れてくるようなものを作ること。日々向かい合う轆轤の隣には、およそ1年前から入門した弟子が座っている。

「誰でもええっていうわけではないと思うんです。うちの仕事にある程度の魅力というか、こういうものを作りたいって思った人でないと。彼は民芸の仕事に憧れがありますから。食事は別なんですけれども(笑)、家内の実家が空いていたんで、そこに住んでもらってます」

弟子に何を伝えるのかという質問には、森山さんはあまり多くを語らない。それは、生活の中に滲み出る美意識でしかなく、言葉にできる類いのものではないからかもしれない。けれど森山窯の隅々にまで充満する、独特の空気の中で仕事をすれば、きっと伝わるものがある。

「器は使われることに価値がある。ただ見ることも使われること。そのものを見たら、ほっとするなとか、なんだか力が湧いてくるようなものができればいいなと思います」

河井寛次郎から森山さんに、さらに次の世代へと受け継がれていくものが、きっとそこにはあって、黙々と、ほとんど会話も交わさずに土と向き合っているふたりの背中は、とても満ち足りているように見えた。

「今の時代に合ったものを作りたい」と森山さんは言う。それが今の民芸ではないかと。世の中に有り余るほどのものの中から選ばれるためには、「ただ作ればええっていうもんじゃない」。表面の美しさではなく、中から光が漏れてくるようなものを作ること。日々向かい合う轆轤の隣には、およそ1年前から入門した弟子が座っている。

「誰でもええっていうわけではないと思うんです。うちの仕事にある程度の魅力というか、こういうものを作りたいって思った人でないと。彼は民芸の仕事に憧れがありますから。食事は別なんですけれども(笑)、家内の実家が空いていたんで、そこに住んでもらってます」

弟子に何を伝えるのかという質問には、森山さんはあまり多くを語らない。それは、生活の中に滲み出る美意識でしかなく、言葉にできる類いのものではないからかもしれない。けれど森山窯の隅々にまで充満する、独特の空気の中で仕事をすれば、きっと伝わるものがある。

「器は使われることに価値がある。ただ見ることも使われること。そのものを見たら、ほっとするなとか、なんだか力が湧いてくるようなものができればいいなと思います」

河井寛次郎から森山さんに、さらに次の世代へと受け継がれていくものが、きっとそこにはあって、黙々と、ほとんど会話も交わさずに土と向き合っているふたりの背中は、とても満ち足りているように見えた。

“I was told that before I become a potter I should first become a splendid person. I should first live the life of a person. That is what being a splendid person is. In other words, live truthfully and precisely.” Moriyama-san says, “I want to create things that match the generation.” Current folk craft is not just crafting objects for approval amongst the vast oceans of waste in this world. It is not about the exterior beauty, but crafting objects where light leaks out from the inside.

A new pupil sits next to the potter’s wheel that Moriyama-san uses each day.

“Not just anyone will do. You have to be someone that understands the beauty of this work or has something specific that they want to create. He admires the work in folk craft. Food on the other hand is a different story, haha. He is living in the empty room in my family home.”

Moriyama-san was unable give details about advice for his pupil, because it is an aesthetic sense that happens naturally in every day life and not just simple words. But if you continue to work in this Moriyama Kama, you will certainly learn something.

“Crafted vessels have value when you use them. Just observing them is also using them. I think it is nice you feel revitalized from just observing an object.”

From Kanjiro Kawai to Moriyama-san, and with the next generation that is succeeding the craft, there was a sense of satisfaction observing the two as they devoted themselves to the clay.

A new pupil sits next to the potter’s wheel that Moriyama-san uses each day.

“Not just anyone will do. You have to be someone that understands the beauty of this work or has something specific that they want to create. He admires the work in folk craft. Food on the other hand is a different story, haha. He is living in the empty room in my family home.”

Moriyama-san was unable give details about advice for his pupil, because it is an aesthetic sense that happens naturally in every day life and not just simple words. But if you continue to work in this Moriyama Kama, you will certainly learn something.

“Crafted vessels have value when you use them. Just observing them is also using them. I think it is nice you feel revitalized from just observing an object.”

From Kanjiro Kawai to Moriyama-san, and with the next generation that is succeeding the craft, there was a sense of satisfaction observing the two as they devoted themselves to the clay.

窓に向かって轆轤を挽く師匠と弟子。

緊張感とも違う、独特の空気に満たされている。(*4)

緊張感とも違う、独特の空気に満たされている。(*4)

*4_ Master and apprentice facing the window spinning at their potter’s wheels. It is a special atmosphere, one of satisfaction.

森山雅夫/1940年島根県生まれ。57年に島根県立職業補導所陶磁器科卒業、河井寛次郎の内弟子となる。71年から島根県温泉津の現在地にて森山窯として独立。日本民藝館協会賞など、受賞多数。

Masao Moriyama

born 1940, Shimane prefecture.

Graduated from ceramics department of the Shiname prefecture Ritsu-shokugyou Hodousho in 1957 and became Kanjirou Kawai’s apprentice. Created the Moriyama Kama in Shimane Yunotsu in 1971. Winner of Japan’s Mingei Association award, among others.